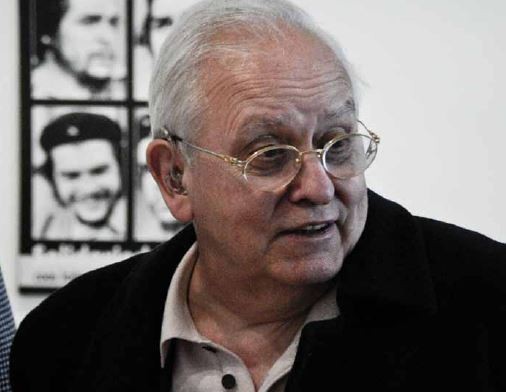

ERNESTO LACLAU

Un pensamiento crítico e innovador

El diario británico The Guardian recuerda al filósofo argentino fallecido el pasado 13 de abril, "cuyas ideas influyeron en las políticas de la nueva izquierda latinoamericana".

Laclau creía que la izquierda europea tenía mucho que aprender de Latinoamérica, dice The Guardian.

Ernesto Laclau, who has died aged 78, was a renowned Argentinian political philosopher whose ideas about "radical democracy" and populism influenced politicians from Latin America's new left as well as activists around the world. His highly original essays and books drew on the work of Antonio Gramsci to probe the assumptions of Marxism, and to illuminate the modern history of Latin America.

With collaborators including his wife, Chantal Mouffe, and the cultural theorist Stuart Hall, Laclau played a key role in reformulating Marxist theory in the light of the collapse of communism and failure of social democracy. His "post-Marxist" manifesto Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (1985), written with Mouffe, was translated into 30 languages, and sales ran into six figures. The book argued that the class conflict identified by Marx was being superseded by new forms of identity and social awareness. This worried some on the left, including Laclau's friend Ralph Miliband, who feared that he had lost touch with the mundane reality of class division and conflict, but his criticisms of Marx and Marxism were always made in a constructive spirit.

Political populism was an enduring fascination for Laclau. His first book, Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory (1977), offered a polite but devastating critique of the conventional discourse on Latin America at the time. This "dependency" approach tended to see the large landowners – latifundistas – as semi-feudal and pre-capitalist, while Laclau showed them to be part and parcel of Latin American capitalism which fostered enormous wealth and desperate poverty. Inequality in Latin America was greater than in any other region of the globe around the year 2000, and is now a little alleviated thanks to the "new left" governments. He rejected the view of some "dependency" theorists – such as Fernando Henrique Cardoso, president of Brazil until 2003 – that Latin America needed more capitalism rather than less.

In 2005, he returned to the theme with On Populist Reason, which helped to explain the rise of the new leftist sentiment sweeping Latin America with the repeated electoral victories of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Néstor Kirchner and his wife in Argentina, and Rafael Correa in Ecuador, among others. Laclau came to be seen as a key influence on Kirchner, with the Argentinian newspaper La Nación reporting breathlessly that the president "made no decision of importance" without first consulting him. While this was a great exaggeration, Kirchner, elected president in 2003, valued Laclau's support in reaching out beyond his Peronista base to the grassroots activists who had been occupying hundreds of factories following the collapse and devaluation of 2001-02. Laclau's sympathy for the Latin American new left was most unwelcome to those who were alarmed by the mobilisation of the poor and excluded.

Indeed, Laclau believed that the European left had much to learn from Latin America, with its spirit of self-criticism and innovation. He argued that the left should not be embarrassed by charges of populism, whether directed at Chávez or at the Greek leftwing party Syriza. It was crucial to distinguish between rightwing populism— for example, Margaret Thatcher's sale of council housing —and policies such as Chávez's gift to shanty-town dwellers of ownership of the land on which they had built. While Thatcherism was mounting a programme of far-reaching privatisation, Chávez was pursuing a plan of "urbanisation" that introduced water and electricity, schools and clinics to the poorest areas, combining self-government with help from tens of thousands of Cuban doctors and teachers.

Born in Buenos Aires, the son of a lawyer and diplomat, also named Ernesto Laclau, and Maria Elena Gastelou, Ernesto studied history at the University of Buenos Aires. He came to Britain in the early 1970s after winning a scholarship to study at Oxford, supported by the historian Eric Hobsbawn. In 1973, he was appointed lecturer in politics at the University of Essex , and it was there that he met Mouffe, whom he married in 1975. The couple pursued their own work but also collaborated on projects, including the series Phronesis, which they co-edited. Mouffe brought to their joint work her own experience with social movements, especially the women's movement.

From 1990 to 1997, Laclau was director of the Centre for Theoretical Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences at Essex, and he became emeritus professor in 2003. He also taught in leading universities in the US, Europe, Scandinavia, Australia, South Africa and Latin America.

In recent years, Laclau contributed frequently to the Argentinian newspaper Página/12, and hosted an interview series for Argentinian TV, Diálogos con Laclau. His quizzical style made him a good interrogator; if a subject said something stupid he would simply repeat it deadpan, perhaps raising an eyebrow.

He is survived by Chantal and three children —Santiago, Soledad and Natalia— from a previous relationship.

Fuente

Publicado originalmente en The Guardian.

Es La Vanguardia que vuelve

La histórica editorial organiza una presentación de sus nuevos títulos, con la participación de los autores.

Búsqueda

Hoy “no mandan los gringos, sino los indios”

Falta completar el cambio y profundizar algunas políticas, dijo Morales.El presidente de Bolivia se comprometió a reducir la pobreza a un dígito en los próximos cinco años. Y destacó la lucha del pueblo, que dejó atrás un estado “colonial, mendigo limosnero” para contar con un país digno.

Editora La Vanguardia celebró su relanzamiento

Oscar González habla en la presentación de su libroCon la presencia de autores, colaboradores, compañeros y amigos, la legendaria editorial socialista dio a conocer sus nuevos títulos.

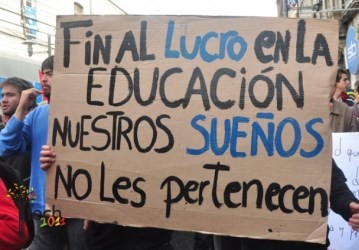

"Hoy pusimos fin al lucro en nuestra educación"

Multitudinarias manifestaciones juveniles reclamaban estos cambios.La presidenta del Senado de Chile destacó la importancia de los cambios aprobados, por los que se regula la admisión, se elimina el financiamiento compartido y se prohíbe el lucro en establecimientos educacionales con fondos del Estado.